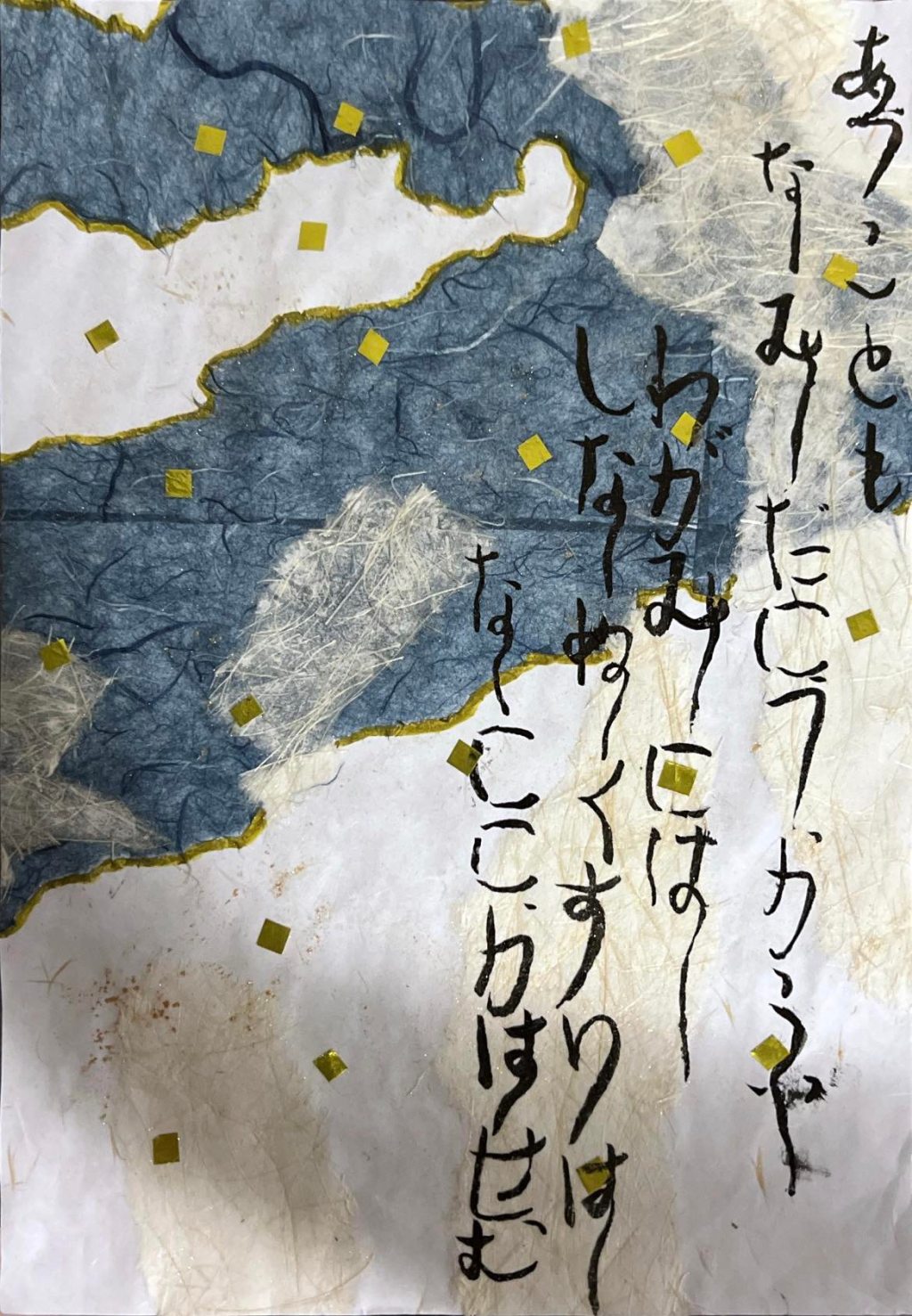

Waka poem from Taketori no Monogatari – Tale of the Bamboo Cutter

Taketori no Monogatari, the Tale of the Bamboo Cutter is one of the oldest known pieces of Japanese literature. It is a story of the girl Kaguya who is found in the stem of a bamboo, is courted by a number of men including the emperor and then is returned to her people who live in the moon.

The origins of the story go back to the 10th century, the most complete version of the story dates from 1650. This translated version is from where I obtained the poem, one of several within the text, which I then transcribed from Romaji into hiragana onto the chigiri-e collage page I had created.

In the following paragraphs, I will discuss the text of Bamboo Cutter in terms of the poetry contained within it, the history of the art of chigiri-e and then into the composition of my own work.

Tale of the Bamboo cutter is an ancient Japanese folk tale about a man who finds a miraculous child named Kaguya inside a bamboo stem, raises her and then, after the touches the heart to the Emperor, she ascends to the moon to be with her true people. The most complete version we have is an illuminated scroll from the 1650 but there are references to the folk tale in other works of literature.

There are a number of versions and translations of Bamboo Cutter but the one I have chosen is from F. Victor Dickin’s 1887 translation of Bamboo Cutter. This perhaps the most complete version that I have found as it is the only one that contains the poetry. These are short waka poems that are said by a character during the story and are usually responded to with another poem by another character with a similar sort of theme. This conversation or game with poetry was a common pastime by aristocrats of the Imperial court during the Heian Period (794 to 1185) and these poems would follow themes of nature and would also reveal personal feelings of the poet. In addition to this, the inclusion of poetry in Japanese folk tales is a fairly common occurrence, though many versions of these tales omit the poems.

The poem I have chosen is the very last one. This poem is said by the Emperor who tells a servant to burn the poem along with the Elixir of Life atop Mount Fuji in the hope that Kaguya who ascended to the moon may receive it. The poem is as follows, first in Romanised Japanese and then in English:

Au koto mo,

namida ni ukabu

waga mi ni wa

shinanu kusuri wa

nani ni ka wa semu?

Never more to see her!

Tears of grief overwhelm me,

and as for me,

with the Elixir of Life

what have I to do?

One interesting note about this poem is that it is one of the few within the story to not have another poem spoken in reply to it by another character. Perhaps there is the hope that Kaguya herself will come down from the moon to reply to his poem.

This poem I chose to display on a chigiri-e collage page using the onna-de calligraphy techniques and these were often used together. Chigiri-e is using torn and cut mulberry paper to create a picture similar to a water colour painting. This is often further embellished with ink painting of pictures or outlines as well as gold and silver leaf and mica powder. A picture may be created that is related to the text that is on the page or may be of a more abstract nature.

This technique was used to decorate the pages of poetry or fiction in bound books but sometimes individual pages were made or even removed from books to make decorative hanging scrolls.

The text on a chigiri-e page was often written using the technique of onna-de, which is a writing style of hiragana which was made for and used by aristocratic Japanese women. Many women were prevented from reading and writing in Chinese, which many religious texts and official documents were written. Onna-de, which translates to “feminine hand”, is far more creative and free-flowing than Chinese script of the time. In onna-de, hiragana characters are sometimes joined together, elongated with variation of their placement on the page and even with the degree the calligrapher presses their brush. These elements are sometimes combined with the picture formed on the page with chigiri-e to further enhance the meaning of the poem. A good example of this, and one I tried to emulate in my own work, is the page from the Shigeyuki poetry pages from the Ishi-Honganji collection.

With my work, I chose the emulate the way that the poem was burnt in the Bamboo Cutter story to suggest that the words were making their way to heaven with the smoke. I have some traditionally made mulberry washi paper which I used with some diluted PVA glue. I tore the paper, sponged it with the glue and placed it on the page to create the sky and smoke leaving white space on the page to suggest the clouds and white snow cap of Mount Fuji. After this I used a gold calligraphy brush pen to outline the blue pieces to get the cloud shape with the white space. I then gave the entire page a light coating of diluted PVA glue with a sponge so that I could lightly dust the page with mica powder and apply small gold metallic squares that I had cut from origami paper.

To compose the text, I experimented a little with placement and elongating of the hiragana characters to suggest they were rising into the air with the smoke. To write the text I used an ink pen with a brush tip similar to a calligraphy brush. I practiced writing this text several times before I put on the decorated page.

In reflection, the page as a whole piece I am quite pleased with. It creates the visual effect that I desired and the material I used were quite good in creating that effect. The calligraphy itself is not something I am pleased with, some of the characters are smeared because my hand brushed against them before the ink was dry and I also consider their formation somewhat crude compared to the delicate examples found in period. However, calligraphy is an art that takes years to master so this would improve with time and proper instruction.

Dickins, F. Victor, The Old Bamboo-Hewer’s Story, Trubner & Co, London, 1888.

Dickins, F. Victor, “The Story of the Old Bamboo-Hewer. (Taketori No Okina No Monogatari.) A Japanese Romance of the Tenth Century.” The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, vol. 19, no. 1, 1887, pp. 1–58. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/25208852. Accessed 12 May 2021.

Keene, Donald, Seeds in the Heart, New York, 1993.

Nippon Gakujutsu Shinkokai, The Manyōshō, Columbia University Press, 1940.

Stanley-Baker, Joan, Japanese Art, Thames & Hudson, London, 2000.

Takenami, Yoko, The Simple Art of Japanese Calligraphy, London, 2004.

Tosa Hiromichi, Taketori Monogatari (竹取物語, The Tale of the Bamboo Cutter) c. 1650, accessed through World Digital Library, https://www.wdl.org/en/item/7354/. Accessed 7/5/2021.

Leave a comment